Mobile payments adoption continues to increase in the United States, and branded mobile payments apps and cards continue to drive usage. Branded cards and apps reward consumers for increased use, which can drive consumer loyalty.

Following that premise, Tyler M. Forbes, community manager at Chicago-based mobile payments startup AeroPay, invited me and Nancy K. Brooks, an attorney at Schuyler Roche Crisham, to participate on a panel at the Flourish branded currency conference, which focuses on branded loyalty and gift-card programs, April 3 in Chicago.

We covered “What Cashless Means for Your Business,” emphasizing the increasing but still nascent trend of stores declining to accept cash for payments. It’s been in the business media in Chicago for some years, as several Chicago retailers stopped accepting cash. As we prepared for the panel, I noticed Goddess and the Grocery, a Chicago chain, had gone cashless as well, with a sign on the window of its store at the corner of La Salle St. and Wacker Drive explaining the decision.

Going cashless means only accepting cards, mobile devices, or branded wrist bands or tokens as a means of payment. From that perspective, store owners have a greater opportunity to use card-based and store-specific mobile apps to cement customer loyalty. That can:

- Increase consumer spend in the store or at an event

- Make fraud detection easier

- Drive loyalty through convenience/great experience/rewards.

- Increase the average lifetime value of a customer,

- Reduce the costs of digital gift card and loyalty programs

To be sure, cashless stores are still a rarity, at least in the U.S., U.K., and E.U. (with the possible exception of Sweden). But their numbers are increasing. And in Asia and Africa, we expect even more cashless consumer activity. In January 2018, for instance, a Wall Street Journal article heralded, “The Cashless Society Has Arrived – Only It’s In China.”

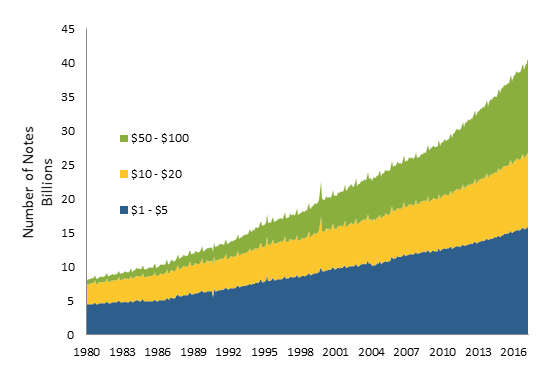

At the same time, cash in circulation continues to grow, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which tracks cash usage in the United States. “Cash remains the most frequently used payment instrument accounting for 31 percent of all consumer transactions.”

Most consumer cash payments are for transactions of less than $10, with “ approximately 60 percent of in-person payments under $were made in cash, compared to 20 percent of in-person transactions for $25 or more. This includes consumers who express a preference for debit-card payments.

Notes in Circulation by Denomination

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

The benefits to retailers, however, can be considerable. Cashless stores can:

- Operate more financially efficient, as the costs of managing cash are expensive, including armored service and employee hands in the till.

- Better tailor the in-store customer experience, product offerings, offer real-time personalized discounts through digital wallets or store-specific apps.

- Provide a safer environment, with less risk of theft for the store owners, employees, and customers.

As Tyler tells it, “My first job out of high school was at a popular clothing brand in the mall. Every night we had to stay well past the mall’s closing time to balance the drawers and deposit the money at the ATM across the street. We were often escorted by a security guard during these deposits. Cashless options negate the need for this entirely.”

More recently, in the U.S. some states and cities have considered banning cashless stores, because they may have a quasi-discriminatory effect, Nancy said. The cashless stores in Chicago tend to be higher-transaction stores. They also tend to be in tonier parts of town, frequented by higher-income consumers, not stores serving recent immigrants who likely run a cash-only economy and don’t have bank accounts.

As Nancy put it, “If you can’t open a bank account, it is challenging to obtain the accounts and access payment products necessary to make an electronic payment transaction. It’s easier to get a mobile phone account in another country than it is to open a bank account or get a payment card in the U.S., due to tighter restrictions on knowing the customer and anti-money laundering laws.” See her post-panel article for additional legal considerations.

What’s a retailer to do? “Survey your customers to see if cashless makes sense for your customers,” Tyler advises. Check the average transaction size, the number of cash transactions, and the likelihood of using mobile apps and rewards to drive cashless transactions. The higher your average transaction, the fewer people you’re going to leave out if you go cashless.

The big problem is that many people do not want to install an app on their phones for each store they frequent. I don’t.

I rarely carry cash, preferring to use a debit card to maintain a budget and a credit-card for business expenses. I do not use mobile apps but conceded during the talk that the rewards points offered by the retailers I frequent will likely push me over the top on that one.

But I do enjoy telling the people who criticize bitcoin and other forms of tokenized payments as tools of criminal payments activity that Franklins (U.S. $100 bills) are the primary form of payment for illicit goods worldwide. Nobody disagrees.

On the other side of the coin, so to speak, I have, since the talk, run into a number of business that only take cash: Sultan’s Market, a Middle Eastern restaurant in Chicago’s Wicker Park, and Sander’s Fresh Dairy, a farm store outside of Chesterton, Indiana, my hometown. For Sander’s, the card fees and POS expense aren’t worth it.

And one of the early retailers in Chicago to go cashless, Sweetgreen, announced it would go back to taking paper for payment, in part because Philadelphia banned cashless stores. Maybe cash is no longer king, but it’s still an important member of the payments royal court.

Download a recap of the Flourish 2019 conference for more trends in branded currency.